This question has been raised by several market commentators, including The Wall Street Journal. Its recent analysis, entitled “Currency Investors: What, Me Worry?” wondered whether the forex markets might not have become too complacent about risk and have seriously underestimated the possibility of another shock.

First, some basics. There are two principal volatility measurements: implied

volatility and realized volatility. The former is so-called because it must be deduced indirectly. In the Black-Scholes model for pricing options, volatility is the only unknown variable and thus is implied by current market prices. It serves as a proxy for investor expectations for volatility over the period for which the option is valid. Realized volatility is of course the actual volatility that is observed in currency markets, calculated based on the size of fluctuations over a given period of time. When fluctuations are greater (whether upward or downward), volatility is said to be high.

For short time frames, implied volatility tends to be very close to realized volatility. For longer time-frames, however, this is not necessarily the case: “The long-dated implied volatilities are often driven to extreme values by one-sided demand or supply – the difference between implied and realised volatilities this causes is particularly large during periods of risk aversion in the market…making implied volatility a particularly poor proxy for realised volatility during periods of market unrest.” In practice, this is reflected by higher prices for long-dated put or call options (depending on the direction of the move that investors are trying to hedge against).

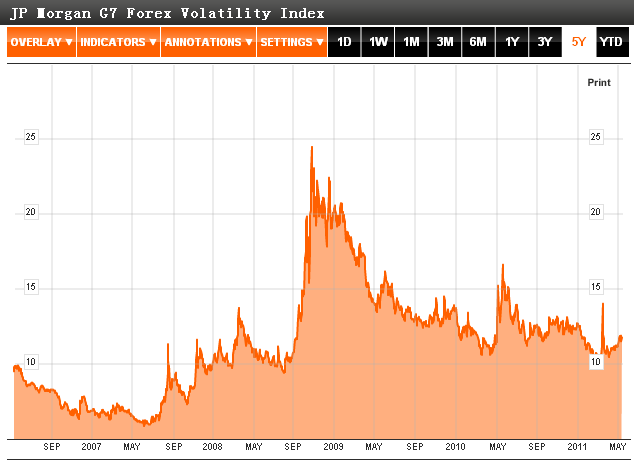

Indeed, most volatility metrics are well below their historical averages and are rapidly closing in on pre-credit crisis levels. This is true for the JP Morgan G7 3-month forex volatility index, the S&P VIX, as well as for specific currencies. Mataf.net (whose content manager I interviewed yesterday) contains replete short-term and long-term data for a few dozen currency pairs, and you can see that almost all of them feature the same downward trend. According to the WSJ, “Investors believe there is a 66% chance each day for the next month that the euro and pound will move no more than 0.6% and 0.5%, respectively—both limited moves.” In addition, “A gauge of the euro’s ‘realized’ volatility, which measures how much daily changes deviate from their recent average, is only 8.6%, lower than its 11% rolling one-year average.”

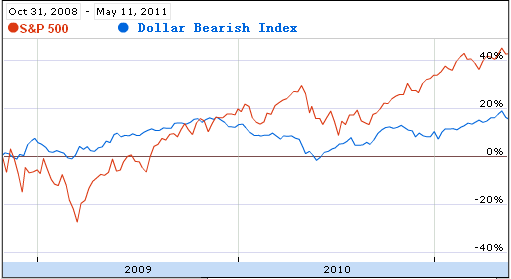

Of course, some commentators don’t see any problem here. They see it both as a positive indication that the markets have returned to normal following the financial crisis, and as a reflection of the correlation that has developed between stock prices and forex markets. (You can see from the chart below the strong inverse correlation between the S&P and the US dollar). According to Deutsche Bank, “Most news that should have shocked the market this year has not managed to do so for sufficiently long to make volatility rise sustainably. Our analytical models tell us that we are indeed moving to a low volatility environment again.”

On the other side of the debate is a growing consensus of investors that sees a pendulum that has swung too far. “I just don’t see how volatility will not increase quite substantially,” said one money manager. “There is significant potential for shocks to the system that currency volatility levels suggest the market is not prepared for,” added another, citing higher commodities prices and inflation, growing public debt, and the imminent end of the Fed’s QE2 monetary stimulus.

To be sure, volatility has started to tick up over the last month. This trend has also been reflected in options prices: “Many investors have avoided buying short-dated currency options this year, instead focusing on longer-dated protection, a phenomenon called a ‘steep volatility curve’…that trend has slowed a bit, with investors moving to hedge against near-term yen, euro and dollar swings.”

Currency traders should start to think about making a few adjustments. Those that think that volatility will continue to rise and/or that the markets are currently underpricing risk can employ a volatility strangle strategy, buying way out-of-the-money puts and calls. The options will pay off if there is a big move in either direction, with no downside risk. Those that think that volatility will continue declining or at least remain at current low levels can make use of the carry trade. Those pairs where interest rate differentials are highest and volatility levels are lowest represent the best candidates. BNP Paribas is also reportedly developing a product that will make it easier for traders to make volatility bets without having to rely on indirect means.

ليست هناك تعليقات:

إرسال تعليق